| Height | 3¾ inches (83 mm) square |

| Case | The square brass case of multi-piece construction, largely retaining its original fire-gilding of superb depth and colour. The step-moulded sides are engraved with geometric bands above arcaded courtyard vistas in perspective and each central arch has a different view: an oak tree, a castle, a windmill and a bridge, each representing an allegorical view of late 16th century London. The latched gilt-brass base panel has a multiple-line engraved border and is signed VALLEN within a beautiful scroll engraved cartouche. The square gilt-brass top plate has engraved fan spandrels flanking a re-instated bezel holding a restored pierced, arcaded and engraved cupola bell cover. |

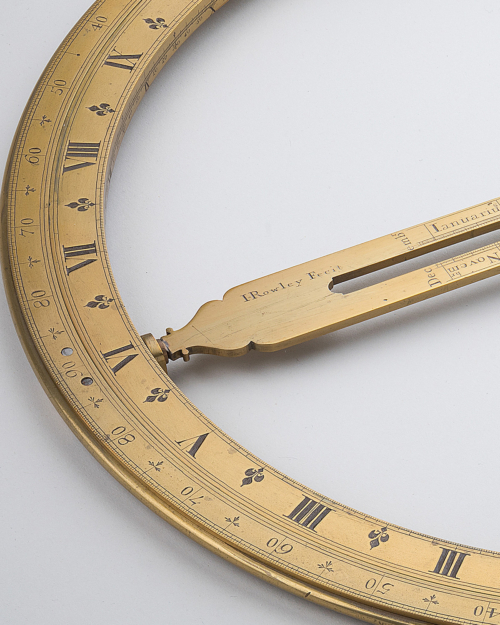

| Dial | The original 2¼ inch (56 mm) delicate solid-silver champlevé Roman chapter ring has flower-head half hour markers, surrounding a further gilt Arabic 24-hour ring marked from 13 to 24, while the concentrically engraved centre is interspersed with arcades and foliage and central steel counterpoised arrow-head hand. |

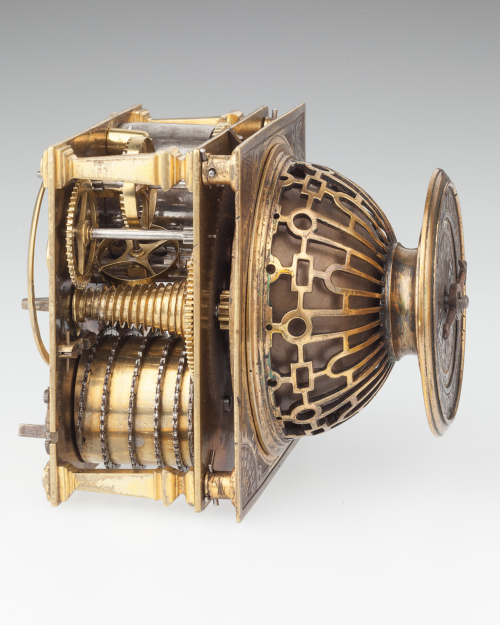

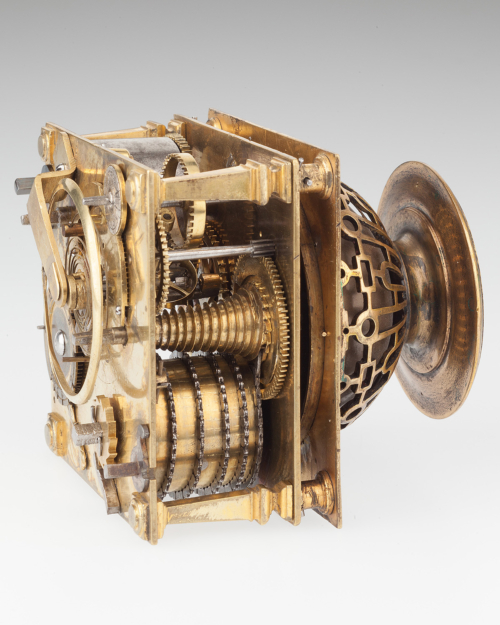

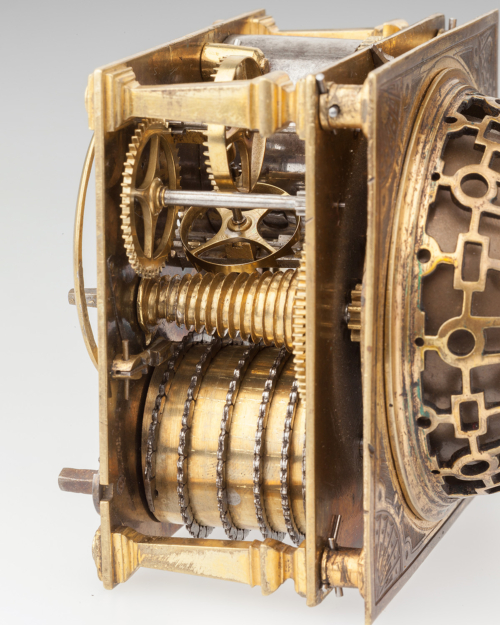

| Movement | The fire-gilded square movement plates are held by four detailed square section baluster pillars, the going train has a fusee and verge escapement, with restored barrel, balance cock and brass balance. The strike train has a fixed steel barrel and calibrated gilt-brass countwheel for striking on the re-instated bell. The backplate retains much of the original gilding and secures to the case with steel turn catches. |

| Duration | 30 hours |

| Provenance | The Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, Jacksonville, Florida, USA, until sold; Christie’s, 19 Nov 2009, lot 21 for £79,250; Private collection UK until sold 2018 for £130,000; John C Taylor Collection, inventory no.190 |

| Comparative Literature | Dawson, Drover & Parkes, Early English Clocks, 1982, p.25, pls.16-18; Lloyd, The Collector’s Dictionary of Clocks,1964, p.182, fig. 463; Garnier & Hollis, Innovation & Collaboration, 2018 |

| Literature | The Luxury of Time, Clocks from 1550-1750, 2019, p.8 |

| Escapement | Restored verge and balance |

| Strike Type | Countwheel hour |

| Exhibited | The Cummer Museum, Jacksonville, Florida, USA 2019-20, The Luxury of Time, Nat. Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, exhibit no.1:3 |

Exhibit № 2: The Cummer Vallin. Circa 1595

An exceedingly rare Elizabeth I engraved gilt-brass striking square horizontal table clock by Nicholas Vallin, London

£135,000

The Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens was built on the site of the home of Arthur and Ninah Cummer, and opened in November 1961. From Ninah Cummer’s relatively small collection of sixty pieces that launched the museum, the permanent collection has now expanded to over five and a half thousand works of art, encompassing eight thousand years of art history.

Nicholas Vallin or Vallen (circa 1565-1603) was the second son of John Vallin (c.1535-1603), a Flemish clockmaker, originally from Ruyssell (now Lille). He married Elizabeth Rendmeesters in 1590 at the Dutch Reformed Church, Austin Friars, and they had three daughters. Nicholas worked first with his father and is then believed to have set up on his own in St Annes, Blackfriars in 1593. He died soon after his father, of the plague on 17 September 1603, and his widow remarried in 1604 to Gerart Cosin, a tailor.

The earliest recorded English domestic clocks were mainly made by Netherlandish immigrants from Flanders and all known examples date from post 1575. There are perhaps only fifteen or sixteen pre-pendulum English spring clocks known to survive and, like the Cummer Vallin, most have had an element of restoration, but many are either missing their original movements or cases altogether. A number of these surviving clocks were made by Nicholas Vallin and the earliest known English clock with a carillon, dated 1598, is also by him, formerly part of the Ilbert Collection, and now found in the British Museum (inventory no.1006.2139).

Only three square table clock by Vallin are recorded and each are very closely related in design:

1. Musée international d’horlogerie, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland.

2. The Portland Collection Museum, the Harley Gallery, Welbeck, Notts.

3. This example, formerly at The Cummer Museum, Jacksonville, Florida.

There are numerous similarities between the Chaux-de-Fonds, Portland and Cummer clocks. All have superb and related engraving to the sides, including geometric bands above arcaded courtyard scenes in perspective. The upper, top-plate sections of the cases all have engraved fan spandrels and similar engraving to the dial centres. The chapter ring of the Portland clock is similarly engraved with Roman chapters and flowerhead half hour markers and an inner 24-hour ring, while the La Chaux-de-Fonds Vallin is recorded as having a later dial, however, it would appear from the other two surviving examples, that only the chapter ring may have been changed. The base plates to all the clocks have square and circular line engraved borders and all are signed VALLEN within similar engraved shield cartouches. While a very similarly engraved dial centre may be seen on a watch by Gylles van Ghele dated 1589 (David Thompson, Watches, British Museum Press, London 2008, p.21).

When the Cummer clock came up for sale in 2009, the original central dial and chapter ring had at some time been lowered onto the box case’s square horizontal top plate, and it was thus a striking clock, but without a corresponding bell, or pierced and arcaded bell assembly. As mentioned, although itself with restored elements, the Chaux-de-Fonds clock had been first illustrated by FJ Britten in 1899 (Old Clocks and Watches) and the design of that bell assembly was used as a template to restore the current example, which is also entirely reversible.

There are six other spring clocks signed by Vallin, known to have survived:

1. Vertical table clock case only (later dial and movement), dated 1600, The British Museum, London (inventory no.1902,0617.1);

2. Monstrance clock (formerly a drum table clock), previously on loan to The British Museum, London;

3. Small drum table clock with astronomical indications, The Science Museum, London (inventory no.1938-429)

4. Small astronomical drum clock (later case), formerly The Time Museum, Illinois, now in the John C Taylor Collection (inventory no.89);

5. Small drum timepiece (with later geared movement and globe), The Banff Museum, Aberdeenshire;

6. Small drum striking clock with alarm, illustrated in ‘Early English Clocks’, 1982, p.21, pl.8.

By the time this clock was made, Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) had been on the throne for nearly 40 years; she had become celebrated for her virginity, and a cult of personality had grown around her which was celebrated in the portraits, decoration (as seen here), pageants, and literature of the day. The period is famous for the flourishing of English drama, led by playwrights such as William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, and for the prowess of English maritime adventurers such as Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh. Some historians depict Elizabeth as a quick-tempered and sometimes indecisive ruler, who enjoyed more than her fair share of luck and, towards the end of her reign, a series of economic and military problems did weaken her popularity.

However, her long reign (1558-1603) soon became renowned as the Elizabethan era, and she is acknowledged as a charismatic leader and a dogged survivor at a time when government was ramshackle and limited, and when monarchs in neighbouring countries faced internal problems that jeopardised their thrones. After the short and unsteady reigns of her half-siblings, her 44 years on the throne (1558-1603) provided welcome stability for the kingdom and helped to forge a sense of national identity. The central scenes (opposite) contained in each individual panel of this clock epitomise this and, taken together, all proclaimed Queen Elizabeth’s deep-rooted and fundamental right to the English crown:

The castle represents authority, dominance, power, romance, safety, sovereignty, and wealth.

The oak tree is symbolic of longevity, strength, stability, endurance, fertility, power, justice, and honesty.

The windmill is a universal symbol of life, hope, serenity, resilience, self-sufficiency, and perseverance.

The bridge embodies the passage (or ascension) from one state to a higher one.

The use of a windmill is particularly interesting, as there were a number of windmills surrounding London at this time, but most were located well outside the City in the environs of Acton, Barnes, Battersea, Blackheath, Chiswick, Finchley, Fulham, Hampstead, Harrow, Richmond, Romford and Rotherhithe. Others had been established in Clerkenwell, Holborn, Kensington (Hyde Park), Mayfair, Newington, Soho, Southwark, Hanover Square, St. James, Westminster and Whitechapel. However it may be more relevant that two new windmills were built in the City in 1596; one was at Queenhithe by the river, while the other was erected near Vallin’s own workshop in Blackfriars, and perhaps this new windmill may have been further inspiration for this particular panel scene.

Product Description

The Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens was built on the site of the home of Arthur and Ninah Cummer, and opened in November 1961. From Ninah Cummer’s relatively small collection of sixty pieces that launched the museum, the permanent collection has now expanded to over five and a half thousand works of art, encompassing eight thousand years of art history.

Nicholas Vallin or Vallen (circa 1565-1603) was the second son of John Vallin (c.1535-1603), a Flemish clockmaker, originally from Ruyssell (now Lille). He married Elizabeth Rendmeesters in 1590 at the Dutch Reformed Church, Austin Friars, and they had three daughters. Nicholas worked first with his father and is then believed to have set up on his own in St Annes, Blackfriars in 1593. He died soon after his father, of the plague on 17 September 1603, and his widow remarried in 1604 to Gerart Cosin, a tailor.

The earliest recorded English domestic clocks were mainly made by Netherlandish immigrants from Flanders and all known examples date from post 1575. There are perhaps only fifteen or sixteen pre-pendulum English spring clocks known to survive and, like the Cummer Vallin, most have had an element of restoration, but many are either missing their original movements or cases altogether. A number of these surviving clocks were made by Nicholas Vallin and the earliest known English clock with a carillon, dated 1598, is also by him, formerly part of the Ilbert Collection, and now found in the British Museum (inventory no.1006.2139).

Only three square table clock by Vallin are recorded and each are very closely related in design:

1. Musée international d’horlogerie, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland.

2. The Portland Collection Museum, the Harley Gallery, Welbeck, Notts.

3. This example, formerly at The Cummer Museum, Jacksonville, Florida.

There are numerous similarities between the Chaux-de-Fonds, Portland and Cummer clocks. All have superb and related engraving to the sides, including geometric bands above arcaded courtyard scenes in perspective. The upper, top-plate sections of the cases all have engraved fan spandrels and similar engraving to the dial centres. The chapter ring of the Portland clock is similarly engraved with Roman chapters and flowerhead half hour markers and an inner 24-hour ring, while the La Chaux-de-Fonds Vallin is recorded as having a later dial, however, it would appear from the other two surviving examples, that only the chapter ring may have been changed. The base plates to all the clocks have square and circular line engraved borders and all are signed VALLEN within similar engraved shield cartouches. While a very similarly engraved dial centre may be seen on a watch by Gylles van Ghele dated 1589 (David Thompson, Watches, British Museum Press, London 2008, p.21).

When the Cummer clock came up for sale in 2009, the original central dial and chapter ring had at some time been lowered onto the box case’s square horizontal top plate, and it was thus a striking clock, but without a corresponding bell, or pierced and arcaded bell assembly. As mentioned, although itself with restored elements, the Chaux-de-Fonds clock had been first illustrated by FJ Britten in 1899 (Old Clocks and Watches) and the design of that bell assembly was used as a template to restore the current example, which is also entirely reversible.

There are six other spring clocks signed by Vallin, known to have survived:

1. Vertical table clock case only (later dial and movement), dated 1600, The British Museum, London (inventory no.1902,0617.1);

2. Monstrance clock (formerly a drum table clock), previously on loan to The British Museum, London;

3. Small drum table clock with astronomical indications, The Science Museum, London (inventory no.1938-429)

4. Small astronomical drum clock (later case), formerly The Time Museum, Illinois, now in the John C Taylor Collection (inventory no.89);

5. Small drum timepiece (with later geared movement and globe), The Banff Museum, Aberdeenshire;

6. Small drum striking clock with alarm, illustrated in ‘Early English Clocks’, 1982, p.21, pl.8.

By the time this clock was made, Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) had been on the throne for nearly 40 years; she had become celebrated for her virginity, and a cult of personality had grown around her which was celebrated in the portraits, decoration (as seen here), pageants, and literature of the day. The period is famous for the flourishing of English drama, led by playwrights such as William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, and for the prowess of English maritime adventurers such as Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh. Some historians depict Elizabeth as a quick-tempered and sometimes indecisive ruler, who enjoyed more than her fair share of luck and, towards the end of her reign, a series of economic and military problems did weaken her popularity.

However, her long reign (1558-1603) soon became renowned as the Elizabethan era, and she is acknowledged as a charismatic leader and a dogged survivor at a time when government was ramshackle and limited, and when monarchs in neighbouring countries faced internal problems that jeopardised their thrones. After the short and unsteady reigns of her half-siblings, her 44 years on the throne (1558-1603) provided welcome stability for the kingdom and helped to forge a sense of national identity. The central scenes (opposite) contained in each individual panel of this clock epitomise this and, taken together, all proclaimed Queen Elizabeth’s deep-rooted and fundamental right to the English crown:

The castle represents authority, dominance, power, romance, safety, sovereignty, and wealth.

The oak tree is symbolic of longevity, strength, stability, endurance, fertility, power, justice, and honesty.

The windmill is a universal symbol of life, hope, serenity, resilience, self-sufficiency, and perseverance.

The bridge embodies the passage (or ascension) from one state to a higher one.

The use of a windmill is particularly interesting, as there were a number of windmills surrounding London at this time, but most were located well outside the City in the environs of Acton, Barnes, Battersea, Blackheath, Chiswick, Finchley, Fulham, Hampstead, Harrow, Richmond, Romford and Rotherhithe. Others had been established in Clerkenwell, Holborn, Kensington (Hyde Park), Mayfair, Newington, Soho, Southwark, Hanover Square, St. James, Westminster and Whitechapel. However it may be more relevant that two new windmills were built in the City in 1596; one was at Queenhithe by the river, while the other was erected near Vallin’s own workshop in Blackfriars, and perhaps this new windmill may have been further inspiration for this particular panel scene.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 5827373 cm |

|---|