| Height | Sundial: 21 inches, plinth: 51 inches (1296 mm) high, overall height: 59 inches (1500 mm) |

| Case | The Base: The very fine octagonal section baluster shaped Portland stone pedestal attributed to the sculptor, John van Nost the Elder (c.1655-c.1711), in three joined elements; the top with circular moulded nosing, faceted below and stepping down to the long concave neck above the octagonal convex main baluster section, with the monogram HK under an earl’s coronet (for Henry Grey, 12th Earl of Kent) sculpted on four faces corresponding with the cardinal points on the dial; all supported on a further octagonal step-graduated, concave to convex, moulded stone foot. |

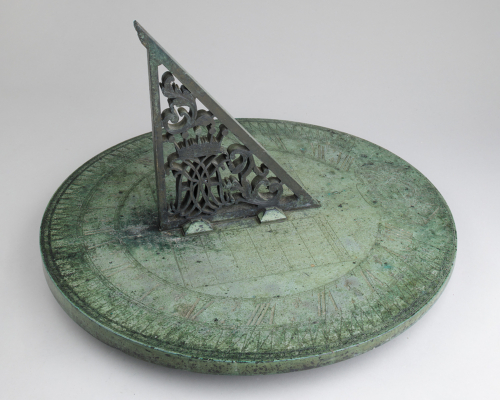

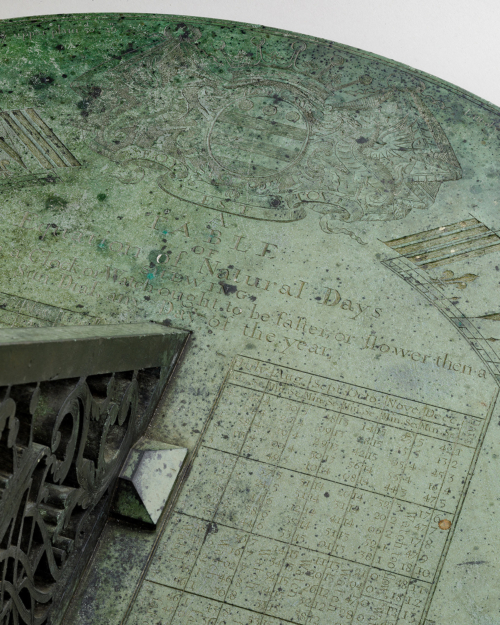

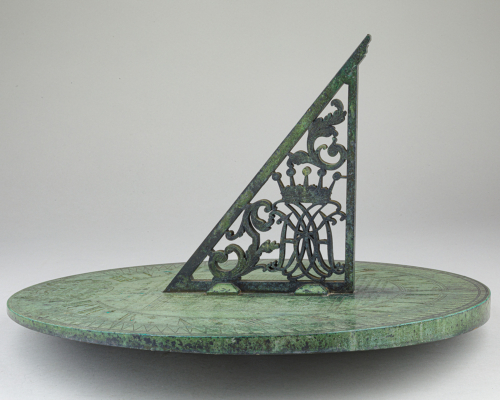

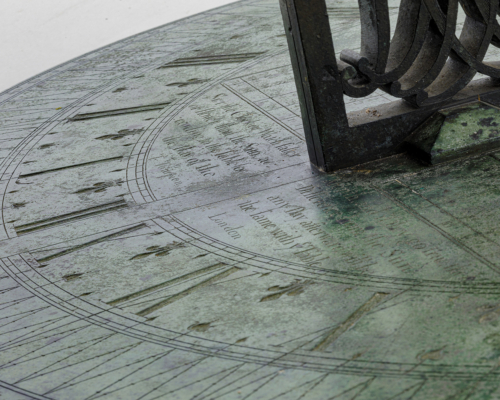

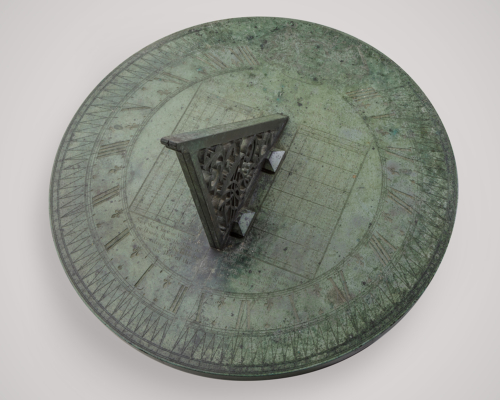

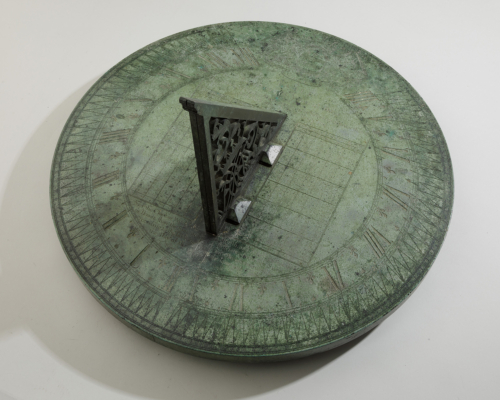

| Dial | The large bronze circular horizontal sundial signed T. Tompion London made for, and bearing the Arms of, Henry Grey, as 12th Earl of Kent. When positioned correctly, the dial reads from the North, looking South, the cast baseplate tapering in that direction, and thus apparently constructed for use in two locations, and further inscribed ‘Latt of ye upper plain 50d 26m’ and ‘Latt of ye under plain 52d 8m’, the latter for Wrest Park in Bedfordshire. The triangular, cast open-work gnomon with truncated pyramidal feet, the pierced decoration incorporating the reflective monogram HK surmounted by an earl’s coronet for Henry Grey, 12th Earl of Kent, with elaborate cast and engraved leaf forms above and below. The dialplate with the arms of Grey, with supporters, device and earl’s coronet, engraved below the south end of the gnomon with the latitude explanations along the edge on either side, and flanked by the hour scale, divided to half-quarters, the scale centre with Roman hours, lozenge quarter-hour marks and decorative fleur-de-Lys half-hour markers laid out clockwise; from IIII to XII for the morning on the West side and; XII to VIII for the afternoon on the East side, the reading further assisted by transversal lines out to the minute division ring around the outer edge, graduated to single minutes and marked with internal Arabic numerals every 10 minutes. The central body of the dial is occupied by A TABLE of Equation of Natural Days SHEWING How much a Clock or Watch ought to be Fafter or Slower then a Sun Dial, any Day of the Year’, with the tabulated equation of time, showing adjustment from true-solar to mean-solar time, in minutes and seconds, every day of the year; from January to June on the East side of the gnomon and; July to December on the West. Below the table are the instructions for its use: ‘Set the Clock or Watch faster or slower than the Sun ac=cording to the Table for any Day of the Month, and if they go true, then Difference from the Sun any Day afterward will be the same with ye Table’. |

| Provenance | Originally made for Henry Grey, 12th Earl of Kent, 2nd Baron Lucas (1671-1740), and created Marquess of Kent, Earl of Harold and Viscount Goderich in 1706, and 1st Duke of Kent in 1710. The sundial and base made for his gardens at Wrest Park, Bedfordshire, thence by descent to his granddaughter; Jemima Yorke, 2nd Marchioness Grey and Countess of Hardwicke, 4th Baroness Lucas (1723-1797) to her daughter; Amabel Hume-Campbell, 1st Countess de Grey, 5th Baroness Lucas (1751-1833) to her nephew; Thomas de Grey, 2nd Earl de Grey, 3rd Baron Grantham, 6th Baron Lucas (1781-1859) to his daughter; Lady Ann Florence de Grey, Countess Cowper, 7th Baroness Lucas (1751-1833) to her son; Francis Thomas de Grey Cowper, 7th Earl Cowper, 8th Baron Lucas (1834-1905) to his nephew; Auberon Thomas Herbert, 9th Baron Lucas and 5th Lord Dingwall (1876-1916), to his sister; Nan Ino Cooper, 10th Baroness Lucas (1880-1958), who sold Wrest Park after the death of her brother in 1917 to; J G Murray Esq. who eventually removed much of the garden statuary, including this sundial, and thence by descent until sold; Sotheby’s, London, 15th June, 2004, lot 46; John C Taylor Collection, inventory no.126 |

| Literature | RW Symonds, Thomas Tompion, his life and work, 1951; Rupert Gunnis, Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660-1851, revised edition, 1964, 279-82; Nicloa Smith, Wrest Park, English Heritage, London, 1995; John Davis, ‘The Equation of Time as shown on Sundials’, Bulletin of the British Sundial Society, xvi, 2003, p.135-44; Jeremy Evans, Thomas Tompion at the Dial and Three Crowns, 2006, listed p.108; The Journal of Garden History, 2012, Linda Halpern, ‘The Duke of Kent’s garden at Wrest Park’; Evans, Carter & Wright, Thomas Tompion 300 Years, 2013, p.557-558, listed p.634; Garnier & Hollis, Innovation & Collaboration, 2018, p.370-371 |

| Diameter | 535 mm |

Exhibit № 28: The Kent Tompion Sundial. Circa 1705

An exceedingly important Queen Anne bronze horizontal sundial by Thomas Tompion, London, on a carved stone plinth attributed to John van Nost the Elder, commissioned by the 12th Earl, later 1st Duke of Kent

£250,000

Only five Tompion garden sundials are known to survive: two in the Royal Collection (RCIN 11959 and 95190) made as a pair for William III in 1699, for the Privy gardens at Hampton Court Palace; this example, The Kent Tompion sundial, c.1705 from Wrest Park, Bedfordshire; The Pump Room Tompion sundial in Bath, c.1709; and The Pelham Tompion sundial, c.1710 (also from this collection, inventory no.109).

This is not only the largest of the known sundials by Tompion, but it is the only example known with a gnomon pierced and engraved for the original owner (see opposite), and the last surviving sundial left in private hands complete with its original, commissioned, Portland stone base. It is also the only example bespoken for two latitudes, operating correctly on the current original pedestal at Wrest Park in Bedfordshire, calibrated for ‘Latt of ye under plain 52d 8m’. The tapered bronze plate appears to allow for a secondary pedestal whose top compensated for that taper, for use on ‘Latt of ye upper plain 50d 26m’; an East/West parallel that dissects Southern England, from Torquay on the Devon coast through the northern outskirts of modern Plymouth to just north of Newquay on the Cornish coast. In 1702, the 12th earl inherited the Lucas barony through his mother with lands near Topsham in Devon, and the current sundial might suggest that he had plans to develop this, or another estate, that never came to fruition.

It seems likely that this dual location feature was more of a novelty attraction than a cost saving; we know that Tompion charged £16 in 1707 to Thomas Coke (1674-1727) for a large brass horizontal dial, for his seat at Melbourne in Derbyshire, but that dial is lost. However, its modest price and lack of ‘equation’ description, suggests Coke’s dial was a simpler affair without an expensive engraved table. In the same bill was watch no.274, and table clock no.430, so perhaps the sundial was to accompany the (now re-cased) Tompion year-going longcase movement, still in the house at Melbourne. Certainly, the dual location taper alone on this example would have cost a deal more. We are also aware that van Nost was charging Coke between £30-£45 for sculptural figures, and thus the original value of the two elements combined is unlikely to have exceeded £75; a sum that the earl could easily have afforded again for a secondary seat.

Thomas Tompion (1639-1713) started numbering his regular output of clocks in c.1681/2 (Thomas Tompion 300 Years, p.148-152), which gives us an insight into the development of his productions. Tompion took Edward Banger into partnership in c.1701 and the items produced switched, over time, to a dual signature. However, the partnership came to an abrupt end in c.1707/8 with Banger being dismissed for reasons unknown, and afterwards there appears to have been a concerted effort to revert to Tompion’s signature alone, the valuable batch-made stock, such as partnership signed longcase dials, were overlaid with new solo signature plaques.

In apparent emphasis of this, some items that returned to the workshop for repair had Banger’s name physically removed and overlaid with updated signature plaques.

As indicated by his arms, cyphers and earl’s coronets, this sundial was originally bespoken for Henry Grey, while he was 12th earl of Kent; he succeeded his father to the earldom in 1702, was elevated to marquess in 1706, and created duke in 1710. That this dial is signed for Tompion alone, might ordinarily imply that it was produced outside his partnership with Banger (c.1701-c.1707), however the use of an earl’s, rather than a higher status marquess’s coronet, apparently narrows the date of production to within the partnership: between Henry Grey’s succession in 1702 and elevation in 1706. At this time, Leonard Knyff painted two views of Wrest House and the park, which Jan Kip engraved, on the closer view there is a sundial clearly depicted (Kip and Knyff, Britannia Illustrata, 1708, plate 18), and although Henry Wynne had produced a sundial dated 1682 for Grey’s father, the 11th Earl (1645-1702), it seems probable that his own, new and fashionable Tompion sundial, on van Nost’s base adorned with his own earl’s cyphers, was the one placed, and illustrated, front and centre.

In 1704, Col. William Parsons, who had known links to engraving in the horological trade, published A New Book of Cyphers… wherein the whole Alphabet… is variously changed, inter-woven, and reversed. Both designs of HK cypher, used in the gnomon and sculpted on four facets of the pedestal, could be argued as having derived from Parson’s design on p.25, no.199, but adapted and simplified. Meanwhile, the equation table engraved at the centre of the dial is laid out in similar manner to the square Pelham Tompion sundial c.1710 (also in this collection, inventory no.109), but as that dial is considerably smaller, values were provided only for every two days. At 21 inches diameter, the present sundial is the largest recorded, giving greater reading accuracy, while its equation table offers a full month set.

John van Nost the Elder (c.1655-c.1711) was a native of Mechelen in the Flemish region of what is now Belgium. He is first recorded in England in around 1679, working as assistant to his fellow Flemish sculptor, Arnold Quellin (1653-1686), at Windsor Castle under the architect, Hugh May (1621-1684). After Quellin’s death in 1686, van Nost married his widow Frances, the youngest daughter of the Antwerp landscape painter Jan Siberechts (1627-1703). By 1687 John van Nost had established his own sculptural workshops, located in Portugal Street, on the site of what is now 105 Piccadilly, near to Hyde Park Corner. There he manufactured Marble and Leaden figures Busto’s and noble Vases Marble chimneypieces and curious Marble tables. John van Nost is perhaps most famous for his lead garden statuary, notably the figures made for Melbourne Hall in Derbyshire that generally cost between £20-30, but he also supplied fireplaces within the house. He produced stone sculpture for Hampton Court, Castle Howard, Buckingham Palace and Chatsworth, and also provided marble tables for the Duke of Devonshire. He additionally undertook impressive funerary monuments in marble, such as that to the Duke and Duchess of Queensberry at Durisdeer (Dumfries and Galloway).

John van Nost apparently died in late 1711 and A CATALOGUE OF Mr. Van NOST’s COLLECTION was produced and Sold by AUCTION… on 17April 1712 at his late Dwelling House in Hyde-Park-Road (near the Queen’s Mead-house… this Collection is the most Valuable that ever was Exposed to Sale in this Kingdom. After his death his cousin, John van Nost II, continued the business, eventually dying in 1729 and his son, John van Nost the younger (d.1780), also continued to work as a sculptor and is particularly noted for his work in Ireland, but John van Nost the Elder is generally considered to be the most important of the artistic dynasty.

The pedestal of the present sundial is almost identical in outline form with the pair made for William III for the Privy Gardens at Hampton Court Palace. Although without the additional foliate decoration that those examples carry it may reasonably be attributed to the same hand. The pair of Hampton Court pedestals carry the cypher of William III and are known to have been made by John van Nost the Elder, and like the present example, both were made for sundials by Thomas Tompion. The king first stayed in his new rooms at Hampton Court in October 1699, and it is likely that the garden statuary for his Privy Garden just outside was installed in November 1699, as the king’s new apartments and gardens were being completed. This seemingly confirmed by a letter from Capt. William Winde to Lady Mary Bridgeman on the 2nd November 1699, who states Madam, Mr. Tompion, and Mr Nostte [John van Nost], being gon to Hampton Court it was not possible to send yr Ladyp and exacte acount of yr Ladyps Commands. John van Nost is known to have worked on other items for Wrest Park, supplying at least one surviving pair of monumental lead urns for the gardens in c.1700 to the 11th earl (see previous exhibit no.27, p.182). Given this association of van Nost with the Grey family, the close similarity in form of the three pedestals and that the monograms they carry being placed in exactly the same position on each of them and, finally, that they are all associated with Tompion sundials, an attribution of the Wrest Park pedestal to John van Nost the Elder seems assured.

In seeming confirmation of this, as well as the two Hampton Court Palace sundials for William III, Tompion and van Nost are known to have shared other customers for whom they likely collaborated; a bill survives from Tompion to the Rt. Hon. Thomas Coke (1674-1727) of Melbourne Hall in Derbyshire, stating that he supplied a Gold Rept Watch No 274 striking ye quarters

against ye Finger &c £70 and a Spring Clock Stand and Out Case No 430 £30, but critically the bill also includes a large brass horizontal dial, £16, supplied on 2nd December 1707. This was the exact time that van Nost was completing statuary for Melbourne Hall gardens, which he had been engaged upon since 1700, and included the famous Four Seasons Vase that was apparently presented to Thomas Coke by Queen Anne in 1705. The Coke Tompion sundial is now lost, but with the extensive known work by van Nost, recorded both inside Melbourne Hall as well as its gardens, mean that it was most likely that that sundial too had a van Nost pedestal bespoken for it in London and supplied to Melbourne Hall at the same time.

The gardens at Wrest Park are one of the grandest of the latter 17th and early 18th centuries, showing Dutch influence in some of its key features, as well as political content celebrating William III. During the 1680s and 1690s, the 11th Earl of Kent embarked on major reconstruction of the garden included a large walled garden with basins and fountains, two wildernesses, a terrace walk, fruit trees espaliered against the brick walls, large iron gates and piers decorated with wyverns from the family coat of arms. After a Grand Tour to the Netherlands, Germany and Italy, Henry Grey became the 12th Earl and inherited the estate in 1702. He continued to expand the garden, adding significant new areas to include this sundial, but also focusing his attention on canals and avenues of trees. Documentary evidence indicates that his tree planting was influenced by his experience of Dutch gardens. In 1708, Wrest was one of only four estates that appeared in multiple views in Britannia Illustrata, by Kip and Knyff (see opposite, plate 19).

A number of garden buildings followed, including the grandiose Pavilion by Thomas Archer between 1709 and 1711 (see p.185), and during the 1710s, there were a number of ambitious garden projects, including a basin in which stood a statue of Neptune held up by wyverns. This unusual format indicates that the Neptune Basin was a statement of allegiance to Whig politics and the Glorious Revolution, since Neptune was commonly associated with William III. There is also a statue of William III at Wrest with an inscription to the King’s ‘glorious and immortell memory’ that celebrates the same allegiance. A second marriage in 1729 to Sophia Bentinck, daughter of the Duke of Portland, reinforced the Duke of Kent’s connection with William’s circle and Dutch gardening. The power of Dutch influence at Wrest is the result of a combination of factors, the Duke’s Grand Tour, his rapidly developing status, his position at Court and his second marriage all contributed to a set of circumstances in which his garden was both a public statement of status and allegiance and a private project motivated by a genuine passion for gardening. Among contemporary documents that demonstrate Wrest’s high reputation is the record of a garden tour in 1735, in which the gardens were described as undoubtedly some of ye finest in England. Wrest had already been singled out for praise in 1718 in the Ichnographica Rustica of Stephen Switzer, and John Mackay included it in his Journey through England in 1724 calling it A very magnificent, noble Seat, with large Parks, Avenues and fine Gardens.

In 1737, Wrest was one of the earliest great gardens to be published in a large garden plan by John Rocque (shown on p.185), but by then the sundial appears to have been moved, and was left out of the illustrations.

The Grey family resided at Wrest Park from the Middle Ages until the 20th century and, as can be seen by the given provenance, from 1702 the house passed down together with the Lucas barony (of Crudwell) that had special remainder through the female line. In 1917, Nan Ino Cooper, 10th Baroness Lucas, sold Wrest Park after her brother, the 9th Baron Lucas, had been shot down and killed in action serving with the Royal Flying Corps. The Murray family purchased the house, and before Wrest Park was acquired for the Nation in 1946, various items were removed from the gardens, including the Kent Tompion sundial with its van Nost pedestal, Their descendant later consigned it to Sotheby’s in 2004.

| A List of Tompion Sundials: | DATE | SHAPE | TABLE | SIZE | PEDESTAL | REFERENCE |

| Hampton Court – 1 of a pair with below | 1699 | Circular | Equation | 20½” | John van Nost the Elder | Royal Coll. inv. 11959 |

| Hampton Court – 2 of a pair with above | 1699 | Circular | Equation | 20½” | John van Nost the Elder | Royal Coll. inv. 95190 |

| Wrest Park, Bedfordshire, The Kent Dial – with two latitudes: 52° 8′, Latt of ye under plain for Wrest Park; 50° 26′, Latt of ye upper plain for Cornwall or Devon. |

c.1705 | Circular | Equation | 21″ | John van Nost the Elder | This sundial JCT Pt.III, Exhib.28 |

| Melbourne Hall, Derbyshire – Documentary evidence only , bill to Rt. Hon. Thomas Coke, dated 1707 Dec 2. | 1707 | ‘Brass horizontal’ | None? | ‘Large’ | Van Nost(?), working at Melbourne 1700-11 | British Library Add.Ms. 69976 f.155 |

| Pump Room, Bath | c.1709 | Octagonal | None | 13″? | Modern pedestal | HJ 3:1960, p.166 |

| Halland House, East Sussex, The Pelham Dial | c.1710 | Square | Equation | 12″ | No pedestal | JCT Pt.I Exhib.29 |

Product Description

Only five Tompion garden sundials are known to survive: two in the Royal Collection (RCIN 11959 and 95190) made as a pair for William III in 1699, for the Privy gardens at Hampton Court Palace; this example, The Kent Tompion sundial, c.1705 from Wrest Park, Bedfordshire; The Pump Room Tompion sundial in Bath, c.1709; and The Pelham Tompion sundial, c.1710 (also from this collection, inventory no.109).

This is not only the largest of the known sundials by Tompion, but it is the only example known with a gnomon pierced and engraved for the original owner (see opposite), and the last surviving sundial left in private hands complete with its original, commissioned, Portland stone base. It is also the only example bespoken for two latitudes, operating correctly on the current original pedestal at Wrest Park in Bedfordshire, calibrated for ‘Latt of ye under plain 52d 8m’. The tapered bronze plate appears to allow for a secondary pedestal whose top compensated for that taper, for use on ‘Latt of ye upper plain 50d 26m’; an East/West parallel that dissects Southern England, from Torquay on the Devon coast through the northern outskirts of modern Plymouth to just north of Newquay on the Cornish coast. In 1702, the 12th earl inherited the Lucas barony through his mother with lands near Topsham in Devon, and the current sundial might suggest that he had plans to develop this, or another estate, that never came to fruition.

It seems likely that this dual location feature was more of a novelty attraction than a cost saving; we know that Tompion charged £16 in 1707 to Thomas Coke (1674-1727) for a large brass horizontal dial, for his seat at Melbourne in Derbyshire, but that dial is lost. However, its modest price and lack of ‘equation’ description, suggests Coke’s dial was a simpler affair without an expensive engraved table. In the same bill was watch no.274, and table clock no.430, so perhaps the sundial was to accompany the (now re-cased) Tompion year-going longcase movement, still in the house at Melbourne. Certainly, the dual location taper alone on this example would have cost a deal more. We are also aware that van Nost was charging Coke between £30-£45 for sculptural figures, and thus the original value of the two elements combined is unlikely to have exceeded £75; a sum that the earl could easily have afforded again for a secondary seat.

Thomas Tompion (1639-1713) started numbering his regular output of clocks in c.1681/2 (Thomas Tompion 300 Years, p.148-152), which gives us an insight into the development of his productions. Tompion took Edward Banger into partnership in c.1701 and the items produced switched, over time, to a dual signature. However, the partnership came to an abrupt end in c.1707/8 with Banger being dismissed for reasons unknown, and afterwards there appears to have been a concerted effort to revert to Tompion’s signature alone, the valuable batch-made stock, such as partnership signed longcase dials, were overlaid with new solo signature plaques.

In apparent emphasis of this, some items that returned to the workshop for repair had Banger’s name physically removed and overlaid with updated signature plaques.

As indicated by his arms, cyphers and earl’s coronets, this sundial was originally bespoken for Henry Grey, while he was 12th earl of Kent; he succeeded his father to the earldom in 1702, was elevated to marquess in 1706, and created duke in 1710. That this dial is signed for Tompion alone, might ordinarily imply that it was produced outside his partnership with Banger (c.1701-c.1707), however the use of an earl’s, rather than a higher status marquess’s coronet, apparently narrows the date of production to within the partnership: between Henry Grey’s succession in 1702 and elevation in 1706. At this time, Leonard Knyff painted two views of Wrest House and the park, which Jan Kip engraved, on the closer view there is a sundial clearly depicted (Kip and Knyff, Britannia Illustrata, 1708, plate 18), and although Henry Wynne had produced a sundial dated 1682 for Grey’s father, the 11th Earl (1645-1702), it seems probable that his own, new and fashionable Tompion sundial, on van Nost’s base adorned with his own earl’s cyphers, was the one placed, and illustrated, front and centre.

In 1704, Col. William Parsons, who had known links to engraving in the horological trade, published A New Book of Cyphers… wherein the whole Alphabet… is variously changed, inter-woven, and reversed. Both designs of HK cypher, used in the gnomon and sculpted on four facets of the pedestal, could be argued as having derived from Parson’s design on p.25, no.199, but adapted and simplified. Meanwhile, the equation table engraved at the centre of the dial is laid out in similar manner to the square Pelham Tompion sundial c.1710 (also in this collection, inventory no.109), but as that dial is considerably smaller, values were provided only for every two days. At 21 inches diameter, the present sundial is the largest recorded, giving greater reading accuracy, while its equation table offers a full month set.

John van Nost the Elder (c.1655-c.1711) was a native of Mechelen in the Flemish region of what is now Belgium. He is first recorded in England in around 1679, working as assistant to his fellow Flemish sculptor, Arnold Quellin (1653-1686), at Windsor Castle under the architect, Hugh May (1621-1684). After Quellin’s death in 1686, van Nost married his widow Frances, the youngest daughter of the Antwerp landscape painter Jan Siberechts (1627-1703). By 1687 John van Nost had established his own sculptural workshops, located in Portugal Street, on the site of what is now 105 Piccadilly, near to Hyde Park Corner. There he manufactured Marble and Leaden figures Busto’s and noble Vases Marble chimneypieces and curious Marble tables. John van Nost is perhaps most famous for his lead garden statuary, notably the figures made for Melbourne Hall in Derbyshire that generally cost between £20-30, but he also supplied fireplaces within the house. He produced stone sculpture for Hampton Court, Castle Howard, Buckingham Palace and Chatsworth, and also provided marble tables for the Duke of Devonshire. He additionally undertook impressive funerary monuments in marble, such as that to the Duke and Duchess of Queensberry at Durisdeer (Dumfries and Galloway).

John van Nost apparently died in late 1711 and A CATALOGUE OF Mr. Van NOST’s COLLECTION was produced and Sold by AUCTION… on 17April 1712 at his late Dwelling House in Hyde-Park-Road (near the Queen’s Mead-house… this Collection is the most Valuable that ever was Exposed to Sale in this Kingdom. After his death his cousin, John van Nost II, continued the business, eventually dying in 1729 and his son, John van Nost the younger (d.1780), also continued to work as a sculptor and is particularly noted for his work in Ireland, but John van Nost the Elder is generally considered to be the most important of the artistic dynasty.

The pedestal of the present sundial is almost identical in outline form with the pair made for William III for the Privy Gardens at Hampton Court Palace. Although without the additional foliate decoration that those examples carry it may reasonably be attributed to the same hand. The pair of Hampton Court pedestals carry the cypher of William III and are known to have been made by John van Nost the Elder, and like the present example, both were made for sundials by Thomas Tompion. The king first stayed in his new rooms at Hampton Court in October 1699, and it is likely that the garden statuary for his Privy Garden just outside was installed in November 1699, as the king’s new apartments and gardens were being completed. This seemingly confirmed by a letter from Capt. William Winde to Lady Mary Bridgeman on the 2nd November 1699, who states Madam, Mr. Tompion, and Mr Nostte [John van Nost], being gon to Hampton Court it was not possible to send yr Ladyp and exacte acount of yr Ladyps Commands. John van Nost is known to have worked on other items for Wrest Park, supplying at least one surviving pair of monumental lead urns for the gardens in c.1700 to the 11th earl (see previous exhibit no.27, p.182). Given this association of van Nost with the Grey family, the close similarity in form of the three pedestals and that the monograms they carry being placed in exactly the same position on each of them and, finally, that they are all associated with Tompion sundials, an attribution of the Wrest Park pedestal to John van Nost the Elder seems assured.

In seeming confirmation of this, as well as the two Hampton Court Palace sundials for William III, Tompion and van Nost are known to have shared other customers for whom they likely collaborated; a bill survives from Tompion to the Rt. Hon. Thomas Coke (1674-1727) of Melbourne Hall in Derbyshire, stating that he supplied a Gold Rept Watch No 274 striking ye quarters

against ye Finger &c £70 and a Spring Clock Stand and Out Case No 430 £30, but critically the bill also includes a large brass horizontal dial, £16, supplied on 2nd December 1707. This was the exact time that van Nost was completing statuary for Melbourne Hall gardens, which he had been engaged upon since 1700, and included the famous Four Seasons Vase that was apparently presented to Thomas Coke by Queen Anne in 1705. The Coke Tompion sundial is now lost, but with the extensive known work by van Nost, recorded both inside Melbourne Hall as well as its gardens, mean that it was most likely that that sundial too had a van Nost pedestal bespoken for it in London and supplied to Melbourne Hall at the same time.

The gardens at Wrest Park are one of the grandest of the latter 17th and early 18th centuries, showing Dutch influence in some of its key features, as well as political content celebrating William III. During the 1680s and 1690s, the 11th Earl of Kent embarked on major reconstruction of the garden included a large walled garden with basins and fountains, two wildernesses, a terrace walk, fruit trees espaliered against the brick walls, large iron gates and piers decorated with wyverns from the family coat of arms. After a Grand Tour to the Netherlands, Germany and Italy, Henry Grey became the 12th Earl and inherited the estate in 1702. He continued to expand the garden, adding significant new areas to include this sundial, but also focusing his attention on canals and avenues of trees. Documentary evidence indicates that his tree planting was influenced by his experience of Dutch gardens. In 1708, Wrest was one of only four estates that appeared in multiple views in Britannia Illustrata, by Kip and Knyff (see opposite, plate 19).

A number of garden buildings followed, including the grandiose Pavilion by Thomas Archer between 1709 and 1711 (see p.185), and during the 1710s, there were a number of ambitious garden projects, including a basin in which stood a statue of Neptune held up by wyverns. This unusual format indicates that the Neptune Basin was a statement of allegiance to Whig politics and the Glorious Revolution, since Neptune was commonly associated with William III. There is also a statue of William III at Wrest with an inscription to the King’s ‘glorious and immortell memory’ that celebrates the same allegiance. A second marriage in 1729 to Sophia Bentinck, daughter of the Duke of Portland, reinforced the Duke of Kent’s connection with William’s circle and Dutch gardening. The power of Dutch influence at Wrest is the result of a combination of factors, the Duke’s Grand Tour, his rapidly developing status, his position at Court and his second marriage all contributed to a set of circumstances in which his garden was both a public statement of status and allegiance and a private project motivated by a genuine passion for gardening. Among contemporary documents that demonstrate Wrest’s high reputation is the record of a garden tour in 1735, in which the gardens were described as undoubtedly some of ye finest in England. Wrest had already been singled out for praise in 1718 in the Ichnographica Rustica of Stephen Switzer, and John Mackay included it in his Journey through England in 1724 calling it A very magnificent, noble Seat, with large Parks, Avenues and fine Gardens.

In 1737, Wrest was one of the earliest great gardens to be published in a large garden plan by John Rocque (shown on p.185), but by then the sundial appears to have been moved, and was left out of the illustrations.

The Grey family resided at Wrest Park from the Middle Ages until the 20th century and, as can be seen by the given provenance, from 1702 the house passed down together with the Lucas barony (of Crudwell) that had special remainder through the female line. In 1917, Nan Ino Cooper, 10th Baroness Lucas, sold Wrest Park after her brother, the 9th Baron Lucas, had been shot down and killed in action serving with the Royal Flying Corps. The Murray family purchased the house, and before Wrest Park was acquired for the Nation in 1946, various items were removed from the gardens, including the Kent Tompion sundial with its van Nost pedestal, Their descendant later consigned it to Sotheby’s in 2004.

| A List of Tompion Sundials: | DATE | SHAPE | TABLE | SIZE | PEDESTAL | REFERENCE |

| Hampton Court – 1 of a pair with below | 1699 | Circular | Equation | 20½” | John van Nost the Elder | Royal Coll. inv. 11959 |

| Hampton Court – 2 of a pair with above | 1699 | Circular | Equation | 20½” | John van Nost the Elder | Royal Coll. inv. 95190 |

| Wrest Park, Bedfordshire, The Kent Dial – with two latitudes: 52° 8′, Latt of ye under plain for Wrest Park; 50° 26′, Latt of ye upper plain for Cornwall or Devon. |

c.1705 | Circular | Equation | 21″ | John van Nost the Elder | This sundial JCT Pt.III, Exhib.28 |

| Melbourne Hall, Derbyshire – Documentary evidence only , bill to Rt. Hon. Thomas Coke, dated 1707 Dec 2. | 1707 | ‘Brass horizontal’ | None? | ‘Large’ | Van Nost(?), working at Melbourne 1700-11 | British Library Add.Ms. 69976 f.155 |

| Pump Room, Bath | c.1709 | Octagonal | None | 13″? | Modern pedestal | HJ 3:1960, p.166 |

| Halland House, East Sussex, The Pelham Dial | c.1710 | Square | Equation | 12″ | No pedestal | JCT Pt.I Exhib.29 |

Additional information

| Dimensions | 5827373 cm |

|---|