| Height | 5 feet 7 inches (1700 mm) |

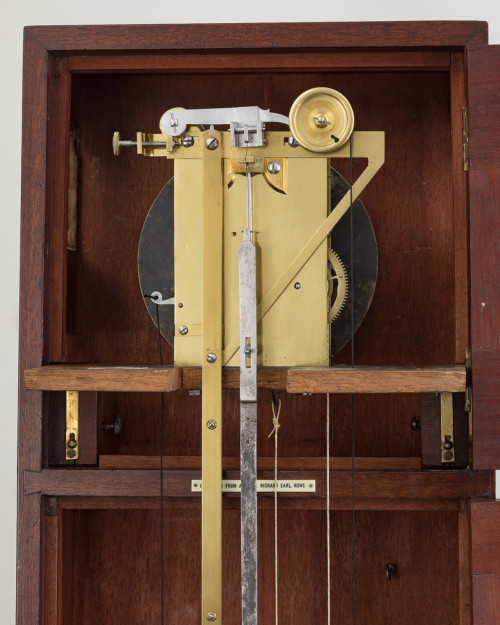

| Case | The tapered pylon-shaped mahogany straight-grained portable case, of simple dovetail-jointed box construction with absolute practicality in mind. The flat top with inset tapering dial door immediately below, mitred to each corner inset with a circular dial aperture and beaded to the edges. The case division rail below, affixed with an ivorine plaque reading Inherited from Admiral Richard Earl Howe, consolidating the case. The full trunk door aperture extending the full width and lower division of the case, the similarly inset beaded trunk door hinged and strengthened with inset mitred cleats top and bottom. The case division rail also supporting the ‘lockable’ movement seatboard, fronted by a slot-in dial mask with integral dust cover. The current mahogany pendulum locking pieces inside the trunk, made specifically to fit the original securing fittings. |

| Dial | The 8 inch (203 mm) circular silvered brass regulator dial, signed Ellicott London, with Arabic minutes outside the division ring, the subsidiary Roman hour sector below centre and subsidiary Arabic seconds ring, 5-60, above centre, all with blued steel hands. |

| Movement | The substantial 6 pillar precision movement, with deadbeat escapement, bolt and shutter maintaining power and Ellicott’s own temperature compensation, mounted to the movement. The lenticular brass bob, with flat iron pendulum rod, fixed to the suspension lever by its suspension spring, through the suspension block cheeks. The iron rod is simultaneously adjusted for expansion/contraction by a compensating flat bi-metallic bar causing the suspension lever to rise or fall by the same amount. |

| Duration | 8 days |

| Provenance | Arguably the well-documented regulator ordered by the Royal Society, and purchased from John Ellicott FRS for £35 8s, for the transits of Venus of 1761 and 1769; |

| Literature | Antiquarian Horology, Spring 1977, Howse, ‘The Admiral’s Clock’, |

| Escapement | Deadbeat with one second pendulum |

Exhibit № 43. Admiral Howe’s Ellicott Regulator, Circa 1760

An historically important and rare George III portable mahogany cased astronomical regulator with Ellicott’s movement-fixed form of temperature compensation

Sold

This transportable Astronomical regulator by John Ellicott FRS was obviously designed specifically for use on voyages of exploration and fitted with one of the two forms of temperature compensation designed and published by Ellicott in the Philosophical Transactions in 1753. But why Admiral Howe should have had such a clock, portable and designed specifically for scientific use, was the subject of Derek Howse article The Admiral’s Clock. He suggests:

Briefly, it seems possible that, perhaps through the interest of his erstwhile Board of Longitude colleagues, he might have been given the opportunity to acquire it from the Royal Society, who disposed of such a clock during the “resting” period between his resignation from the post of Treasurer of the Navy in 1770 and his appointment as Commander-in-Chief North America in 1776.

John Ellicott FRS (1706-1772) was the most talented and celebrated member of the Ellicott dynasty whose businesses endured for 150 years, from the late seventeenth to the mid nineteenth centuries. He was the son of a Cornishman, who had gone to London and was free of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1696. He was born in the parish of All Hallows, London Wall in 1706 and gained his freedom by patrimony in 1726, establishing his own business in c.1728. On his father’s death in 1733 he took over his workshops in Swithin’s Alley staying there throughout his career and, eventually, passing the premises on to his own son, Edward.

The first evidence of Ellicott’s interest in the effects of temperature on metals was his initial submission to the Royal Society in 1736 of his design for an improved pyrometer; The Description and Manner of using an instrument for measuring the Degrees of the expansion of Metals by Heat. On 26th October 1738, at the age of 32, Ellicott was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and his sponsors included the incumbent President, Sir Hans Sloane, as well as Martin Ffolkes (later PRS), John Senex (globemaker) and John Hadley (mathematician and astronomer). The following year Ellicott read two papers to the society giving An Account of the Influence which two Pendulum Clocks were observed to have upon each other. In 1747 he read a series of three Essays towards, discovering the Laws of Electricity and continued to present other papers.

In June 1752 he submitted the Two Methods of his renowned compensated pendulum, reading to the Society A Description of Two Methods by which the Irregularities in the Motion of a Clock, arising from the Influence of Heat and Cold upon the Rod of the Pendulum, may be prevented. In the first paragraph of the paper he claimed to have already offered his thoughts on his compensating pendulum to the Society’s Secretary, John Machin, in 1738. If one was cynical, it was perhaps convenient that John Machin had died the year before Ellicott’s publication and the importance of this statement is that it gave validity to the originality of his pendulum, without actually claiming precedence over Graham’s ‘quicksilver’ and Harrison’s ‘gridiron’ pendulums, although some took that as implied.

George Graham had also died the year before and the backlash was immediate; by November 1752, James Short FRS, who was a friend of Graham’s and owned a regulator by him, had written at length to the Society an account [that] contains nothing but matters of fact citing that both Graham and Harrison had been there first and that John Shelton had informed Short that in 1737 Graham had even made a compensated pendulum on the same ‘lever’ principles used by Ellicott, furthermore This clock still remains in Mr Graham’s house, in the possession of his executors. The dispute continued and by 1753 a summary letter was published in the Gentleman’s magazine, Vol.XXIII, pointing out that the difference of the construction of these several pendulums is only in the manner of applying the same principle. Technically this was absolutely true, there was nothing new in principle in Ellicott’s inventions, however, his updated solution was mechanically ingenious and clearly seen as credible at the time, as Ellicott started to fulfil prestigious regulator commissions, including; a small series of portable regulators, specifically for the 1761 and 1769 Transits of Venus expeditions, of which this clock is perhaps the first and ordered by the Royal Society; as well as longcase regulators, such as the one ordered by Harvard University in c.1765, to replace a clock destroyed in the Harvard Hall fire of 1764, and that remained their primary timekeeper until the 1840s.

However, Ellicott’s temperature compensation story doesn’t quite end there, in the closing paragraph of his address to the Society in June 1752, Ellicott mentioned a watch that, although now lost, might prove to have been a rather more important contribution to horology than his contested compensated pendulum:

Before I conclude this paper, I beg leave to acquaint this honorable Society, that in the year 1748, I made the model of a contrivance to be added to a pocket watch, founded upon the same principles, and intended to answer the like purpose, as the pendulum above described; and at a meeting of a council of this Society, on the fifteenth of February last, I produced a watch (which I had made for a gentleman) with this contrivance added to it, and likewise a model, by which was shown to the gentlemen then present what effect a small degree of heat would have upon it. But as I have not yet had sufficient trial of this watch, I shall defer giving a particular description of this contrivance, till I am fully satisfied to what degree of exactness it can be made, to answer the end proposed.

Ellicott’s claim would make his 1748 model, together with the watch shown to the Society Council on 15th February 1752, the first of their kind fitted with temperature compensation. What form this compensation took is not recorded but by giving an initial date of 1748, Ellicott was conveniently predating Harrison’s description of his bimetallic curb presented to the society in 1749. At this time, Harrison was still convinced a sea ‘clock’ was his answer and the curb was created for H3. Did Ellicott recognise its significance and try to apply a similar principle to his watch? There is nothing to doubt the existence of Ellicott’s watch and the fact that he had shown it to members so soon before, gives it credence. In Marine Chronometers at Greenwich Jonathan Betts argues that it was highly likely that Thomas Mudge made the watch shown to the Council in 1752 and that a later reference by Harrison suggests that it was by then well known that its performance was unsatisfactory. Mudge was working for Ellicott at this time and had made several watches for him that Ellicott had supplied to King Ferdinand VI of Spain. Michael Smith, watchmaker to the Spanish king, had discovered this and, much to Ellicott’s chagrin, had recommended using Mudge direct.

Betts goes on to suggest that, after George Graham died in 1751, there may have been a connection between Mudge and Harrison and the latter could have been inspired by Mudge’s work, which perhaps started with Ellicott’s aforementioned model or watch. What is certain, it was about this time that Harrison commissioned his now famous watch from another of Graham’s watchmakers, John Jefferys, which was completed in 1753 and inspired Harrison to start work on a watch based timekeeper, that eventually became his successful H4.

John Ellicott FRS had built up and maintained a reputation for fine quality clocks and watches and by 1762 he was made Clockmaker in ordinary to King George III, a post he held until his death. He also developed an extensive export business, particularly to the Iberian peninsular, and from early in King Ferdinand VI’s reign, 1746 to 1759, he supplied the Spanish Royal Court with exceptionally fine clocks, watches and other items too, including a terrestrial globe.

John Ellicott died at Hackney in 1772, aged 67, his will was proved on 26th March 1772. He described himself as of the parish of St. John, Hackney, watchmaker, and desired burial in the same vault with my late dear wife. Ellicott had two sons, Edward and John, and three unmarried daughters, he was a protestant nonconformist and he bequeathed £20 to his pastor, a Reverend Palmer, and £10 to the poor of the dissenters’ meeting-house in Mare Street, Hackney.

Richard Howe (1726-1799) joined the Navy as a Midshipman at the age of 15 and rose swiftly in the Service, being promoted to Captain at the age of 20. When in command of the Dunkirk in 1755, in capturing the Alcide off the mouth of the St. Lawrence, he virtually opened the Seven Years’ War, thereafter taking a leading part in the Rochefort expedition in 1757 and commanding the covering squadrons in the attacks on St. Malo and Cherbourg in 1758. He took a distinguished part in the blockade of Brest and the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759.

A Lord of the Admiralty from 1762, he was then Treasurer of the Navy from 1765 to 1770, during which time he was a Commissioner for Longitude attending the various board meetings connected with the later trials of Harrison’s timekeepers and the planning for the 1769 transit of Venus. He was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1770 and in 1772 he bought Porters Lodge, a house near St Albans. Though M.P. for Dartmouth, he held no post in the Royal Navy from 1770, until 1776.

In February 1776, during the American War of Independence (1775–1783), Howe was appointed commander-in-chief of the North America station as he was known to be on good terms with the rebellious Americans, and in particular Benjamin Franklin whom he admired greatly and thought was willing to negotiate. Having left Spithead in May, he joined his brother General Sir William Howe at New York on 12th July 1776. The two Howes had been appointed peace commissioners on 3rd May and were expected to reach a conciliatory arrangement with the rebels but arriving after the Declaration of Independence, they met with the Congress in September and were unable to achieve a breakthrough. Having come to the conclusion that they had spent too much time with negotiations in the face of sheer belligerence, the Howes were thereby obliged to take the war to the Americans.

On 28th June 1776, governmental interference had diverted a strong squadron of ships and four thousand troops to make an ultimately futile attack on the port of Charleston. Nevertheless, Howe co-operated successfully with his brother in the Long Island and New York campaign from July-October 1776. The following summer he conveyed his brother’s army to the Head of the Elk, disembarking on the 25th August 1777 and returning to the Delaware to command the clearance of that waterway. Philadelphia was then captured by his brother and the Delaware River was opened up to the sea, but on hearing that a superior French fleet was crossing the Atlantic, Howe took the larger of his vessels back to New York in December, and Philadelphia was evacuated in the following June.

In the meantime a new peace committee had been set up and Howe, along with his brother, tendered his resignation on 23rd November 1777, bitter at having been seemingly deposed and having not enjoyed support from Lord North’s government. The resignations were accepted on 24th February 1778, but with the caveat that the Admiralty hoped Howe would no longer feel resignation necessary. Before his replacement could be effected his brilliant powers of leadership repelled the Comte d’Estaing’s French fleet, of twice his number, off Sandy Hook in July 1778. When the French sailed for Rhode Island he followed them, arriving on 9th August but refusing to give battle as he did not want to fight on his enemy’s terms. A violent gale dispersed the fleets but not before Howe’s 50-gun ships harried d’Estaing’s bigger ships back to Boston. After returning to Sandy Hook, Howe went back to Boston on 31st August but by now the French fleet was in total disarray and it was with some satisfaction that he was able to leave America on 25th September.

For the next three years he lived at Porters Lodge, whilst he and his brother defended themselves against claims that they had not prosecuted the war to the best of their abilities. Between January and July 1779 there was much debate in the Houses of Parliament over the Howes’ North American campaign, and in a speech he made on 8th March Howe accused Lord North’s government of distributing false pamphlets denigrating him and his brother and, without a doubt, the North administration considered the Howes’ to be excellent and convenient scapegoats.

It was not until after the resignation of Lord North’s administration, that Howe returned becoming commander in the Channel in 1782, and effecting the Relief of Gibraltar that year. From 1783 to 1788, he was First Lord of the Admiralty, but returned to command the Channel Fleet in 1790, winning the great victory of the Glorious First of June in 1794, capturing six French ships. During his service career, he was particularly active on signals and tactics and is said to have been the first person to lay down a positive rule-of-the-road at sea; that a ship on the port tack should give way to one on the starboard tack. Howe ranks with Anson, Hawke, and Rodney as one of the greatest seamen of the 18th century.

Howe succeeded to a Viscountcy in the Irish Peerage in 1758, was created Viscount in the Peerage of Great Britain in 1782 and Earl in 1788.

The transits of Venus of 1761 and 1769 appear to be the start of the story of this portable astronomical regulator. The planet Venus passes directly between the Earth and the Sun twice every 113 years and, for a few hours appears silhouetted, moving across the bright solar disc. If the apparent position of the track relative to the Sun can be determined as seen from several places of widely differing latitudes, this will give a measure of the radius of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, one of the fundamental distances in astronomy.

The predicted transits of 1761 and 1768 were considered one of the most important scientific happenings of the century and gave rise to many expeditions, which were dispatched to remote parts of the world. The 1761 transit was taken particularly seriously by the British and French governments, but also included the Swedish, Russians and Americans. By 1768 interest had grown and the observations increased, again principally organised by the British and French, and including the Swedish, Russians and Americans but involving Catherine the Great overseeing in St Petersburg with Benjamin Franklin in London and David Rittenhouse in Pennsylvania.

The British preparations for the 1761 transit were in the hands of the Royal Society who bought from Ellicott, one of their own Fellows, a timepiece for £35.8s. Nevil Maskelyne and John Waddington were to be the Society’s observers at St. Helena, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon (the same that later gave their names to the Mason-Dixon line between Pennsylvania and Maryland) were to go to Sumatra, and the Ellicott clock was allocated to the second pair.

Mason and Dixon embarked at Spithead in H.M.S. Seahorse, under Captain James Smith, at the end of December 1760. She sailed for Sumatra on January 9th, 1761. But these were troubled times and the Seven Years War (1756-1763) was in progress. The day after sailing, the Seahorse fell in with a French ship and came under attack with 11 killed and 38 wounded. On limping into Plymouth, Mason reported that the instrument stands were hurt very much, but that the clock, quadrant, telescopes, etc., were not damaged. The Seahorse finally sailed from Plymouth with a new captain on February 3rd, 1761, however, so much time had been lost that going to Sumatra had to be abandoned and Mason and Dixon were landed at Cape Town on May 2nd, setting up the Ellicott clock ashore on May 4th. The transit was successfully observed on June 5th. On the way home Mason and the Ellicott clock were landed at St. Helena to continue the gravity experiments which he had made at Cape Town. Here he met Maskelyne who had sent his clock, by Shelton, to the Cape for the same purpose.

In June 1769, the Ellicott clock was once again present at a transit of Venus, this time being set up the previous September at Prince of Wales Fort, Hudson’s Bay in Canada. On 11th December 1768, with an internal temperature of minus 31°F and an external of minus 42°F, the regulator stopped and was not set going again until March 28th when the temperature had risen to about 0°F. On June 3rd, 1769, the transit of Venus was successfully observed using the Ellicott clock for timing by William Wales (c.1734-1798). It is interesting to note that, in the official account, the clock was referred to as a clock, made by Mr Ellicot, with an apparatus for correcting the effects of heat and cold; the same which Messieurs Mason and Dixon had to the Cape of Good Hope.

In May 1771, Dr. Owen and Mr. Maskelyne presented to the Royal Society Council a list of the observatory instruments used in the various transit of Venus expeditions, together with their valuations. Though the list itself cannot be found, the Council minutes do give the valuations, including £38 for each of two Shelton clocks but no mention of the Ellicott. The minutes go on, Ordered that any member of the Society be at liberty within a month to purchase any of them at the specified valuations, except that those that are intended to be kept for use of the Society. On 19th March 1772, the Council ordered that the astronomical instruments, contained in a list with the valuations, be put up for public auction, but there are no further records of the auction or the Ellicott clock.

Although Admiral Howe never took part in a scientific expedition or voyage of exploration, he was Treasurer of the Navy, 1765-1770, attending board meetings connected with the planning for the 1769 transit and perhaps that sparked his interest in a souvenir? It seems likely that, after the success of the first transit observations, Ellicott was commissioned to produce more portable regulators. Stylistically, this clock with its simple circular dial, rectangular plates, interior pendulum adjustment and squared off case corners, has every appearance of being a little earlier than the other surviving examples. Furthermore, Admiral Howe’s clock is the only surviving portable regulator by Ellicott that appears to lead us directly back to the 18th Century, and the characters involved with the Royal Society portable regulator and the transits of Venus, which is possibly the first that Ellicott produced.

Product Description

This transportable Astronomical regulator by John Ellicott FRS was obviously designed specifically for use on voyages of exploration and fitted with one of the two forms of temperature compensation designed and published by Ellicott in the Philosophical Transactions in 1753. But why Admiral Howe should have had such a clock, portable and designed specifically for scientific use, was the subject of Derek Howse article The Admiral’s Clock. He suggests:

Briefly, it seems possible that, perhaps through the interest of his erstwhile Board of Longitude colleagues, he might have been given the opportunity to acquire it from the Royal Society, who disposed of such a clock during the “resting” period between his resignation from the post of Treasurer of the Navy in 1770 and his appointment as Commander-in-Chief North America in 1776.

John Ellicott FRS (1706-1772) was the most talented and celebrated member of the Ellicott dynasty whose businesses endured for 150 years, from the late seventeenth to the mid nineteenth centuries. He was the son of a Cornishman, who had gone to London and was free of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1696. He was born in the parish of All Hallows, London Wall in 1706 and gained his freedom by patrimony in 1726, establishing his own business in c.1728. On his father’s death in 1733 he took over his workshops in Swithin’s Alley staying there throughout his career and, eventually, passing the premises on to his own son, Edward.

The first evidence of Ellicott’s interest in the effects of temperature on metals was his initial submission to the Royal Society in 1736 of his design for an improved pyrometer; The Description and Manner of using an instrument for measuring the Degrees of the expansion of Metals by Heat. On 26th October 1738, at the age of 32, Ellicott was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and his sponsors included the incumbent President, Sir Hans Sloane, as well as Martin Ffolkes (later PRS), John Senex (globemaker) and John Hadley (mathematician and astronomer). The following year Ellicott read two papers to the society giving An Account of the Influence which two Pendulum Clocks were observed to have upon each other. In 1747 he read a series of three Essays towards, discovering the Laws of Electricity and continued to present other papers.

In June 1752 he submitted the Two Methods of his renowned compensated pendulum, reading to the Society A Description of Two Methods by which the Irregularities in the Motion of a Clock, arising from the Influence of Heat and Cold upon the Rod of the Pendulum, may be prevented. In the first paragraph of the paper he claimed to have already offered his thoughts on his compensating pendulum to the Society’s Secretary, John Machin, in 1738. If one was cynical, it was perhaps convenient that John Machin had died the year before Ellicott’s publication and the importance of this statement is that it gave validity to the originality of his pendulum, without actually claiming precedence over Graham’s ‘quicksilver’ and Harrison’s ‘gridiron’ pendulums, although some took that as implied.

George Graham had also died the year before and the backlash was immediate; by November 1752, James Short FRS, who was a friend of Graham’s and owned a regulator by him, had written at length to the Society an account [that] contains nothing but matters of fact citing that both Graham and Harrison had been there first and that John Shelton had informed Short that in 1737 Graham had even made a compensated pendulum on the same ‘lever’ principles used by Ellicott, furthermore This clock still remains in Mr Graham’s house, in the possession of his executors. The dispute continued and by 1753 a summary letter was published in the Gentleman’s magazine, Vol.XXIII, pointing out that the difference of the construction of these several pendulums is only in the manner of applying the same principle. Technically this was absolutely true, there was nothing new in principle in Ellicott’s inventions, however, his updated solution was mechanically ingenious and clearly seen as credible at the time, as Ellicott started to fulfil prestigious regulator commissions, including; a small series of portable regulators, specifically for the 1761 and 1769 Transits of Venus expeditions, of which this clock is perhaps the first and ordered by the Royal Society; as well as longcase regulators, such as the one ordered by Harvard University in c.1765, to replace a clock destroyed in the Harvard Hall fire of 1764, and that remained their primary timekeeper until the 1840s.

However, Ellicott’s temperature compensation story doesn’t quite end there, in the closing paragraph of his address to the Society in June 1752, Ellicott mentioned a watch that, although now lost, might prove to have been a rather more important contribution to horology than his contested compensated pendulum:

Before I conclude this paper, I beg leave to acquaint this honorable Society, that in the year 1748, I made the model of a contrivance to be added to a pocket watch, founded upon the same principles, and intended to answer the like purpose, as the pendulum above described; and at a meeting of a council of this Society, on the fifteenth of February last, I produced a watch (which I had made for a gentleman) with this contrivance added to it, and likewise a model, by which was shown to the gentlemen then present what effect a small degree of heat would have upon it. But as I have not yet had sufficient trial of this watch, I shall defer giving a particular description of this contrivance, till I am fully satisfied to what degree of exactness it can be made, to answer the end proposed.

Ellicott’s claim would make his 1748 model, together with the watch shown to the Society Council on 15th February 1752, the first of their kind fitted with temperature compensation. What form this compensation took is not recorded but by giving an initial date of 1748, Ellicott was conveniently predating Harrison’s description of his bimetallic curb presented to the society in 1749. At this time, Harrison was still convinced a sea ‘clock’ was his answer and the curb was created for H3. Did Ellicott recognise its significance and try to apply a similar principle to his watch? There is nothing to doubt the existence of Ellicott’s watch and the fact that he had shown it to members so soon before, gives it credence. In Marine Chronometers at Greenwich Jonathan Betts argues that it was highly likely that Thomas Mudge made the watch shown to the Council in 1752 and that a later reference by Harrison suggests that it was by then well known that its performance was unsatisfactory. Mudge was working for Ellicott at this time and had made several watches for him that Ellicott had supplied to King Ferdinand VI of Spain. Michael Smith, watchmaker to the Spanish king, had discovered this and, much to Ellicott’s chagrin, had recommended using Mudge direct.

Betts goes on to suggest that, after George Graham died in 1751, there may have been a connection between Mudge and Harrison and the latter could have been inspired by Mudge’s work, which perhaps started with Ellicott’s aforementioned model or watch. What is certain, it was about this time that Harrison commissioned his now famous watch from another of Graham’s watchmakers, John Jefferys, which was completed in 1753 and inspired Harrison to start work on a watch based timekeeper, that eventually became his successful H4.

John Ellicott FRS had built up and maintained a reputation for fine quality clocks and watches and by 1762 he was made Clockmaker in ordinary to King George III, a post he held until his death. He also developed an extensive export business, particularly to the Iberian peninsular, and from early in King Ferdinand VI’s reign, 1746 to 1759, he supplied the Spanish Royal Court with exceptionally fine clocks, watches and other items too, including a terrestrial globe.

John Ellicott died at Hackney in 1772, aged 67, his will was proved on 26th March 1772. He described himself as of the parish of St. John, Hackney, watchmaker, and desired burial in the same vault with my late dear wife. Ellicott had two sons, Edward and John, and three unmarried daughters, he was a protestant nonconformist and he bequeathed £20 to his pastor, a Reverend Palmer, and £10 to the poor of the dissenters’ meeting-house in Mare Street, Hackney.

Richard Howe (1726-1799) joined the Navy as a Midshipman at the age of 15 and rose swiftly in the Service, being promoted to Captain at the age of 20. When in command of the Dunkirk in 1755, in capturing the Alcide off the mouth of the St. Lawrence, he virtually opened the Seven Years’ War, thereafter taking a leading part in the Rochefort expedition in 1757 and commanding the covering squadrons in the attacks on St. Malo and Cherbourg in 1758. He took a distinguished part in the blockade of Brest and the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759.

A Lord of the Admiralty from 1762, he was then Treasurer of the Navy from 1765 to 1770, during which time he was a Commissioner for Longitude attending the various board meetings connected with the later trials of Harrison’s timekeepers and the planning for the 1769 transit of Venus. He was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1770 and in 1772 he bought Porters Lodge, a house near St Albans. Though M.P. for Dartmouth, he held no post in the Royal Navy from 1770, until 1776.

In February 1776, during the American War of Independence (1775–1783), Howe was appointed commander-in-chief of the North America station as he was known to be on good terms with the rebellious Americans, and in particular Benjamin Franklin whom he admired greatly and thought was willing to negotiate. Having left Spithead in May, he joined his brother General Sir William Howe at New York on 12th July 1776. The two Howes had been appointed peace commissioners on 3rd May and were expected to reach a conciliatory arrangement with the rebels but arriving after the Declaration of Independence, they met with the Congress in September and were unable to achieve a breakthrough. Having come to the conclusion that they had spent too much time with negotiations in the face of sheer belligerence, the Howes were thereby obliged to take the war to the Americans.

On 28th June 1776, governmental interference had diverted a strong squadron of ships and four thousand troops to make an ultimately futile attack on the port of Charleston. Nevertheless, Howe co-operated successfully with his brother in the Long Island and New York campaign from July-October 1776. The following summer he conveyed his brother’s army to the Head of the Elk, disembarking on the 25th August 1777 and returning to the Delaware to command the clearance of that waterway. Philadelphia was then captured by his brother and the Delaware River was opened up to the sea, but on hearing that a superior French fleet was crossing the Atlantic, Howe took the larger of his vessels back to New York in December, and Philadelphia was evacuated in the following June.

In the meantime a new peace committee had been set up and Howe, along with his brother, tendered his resignation on 23rd November 1777, bitter at having been seemingly deposed and having not enjoyed support from Lord North’s government. The resignations were accepted on 24th February 1778, but with the caveat that the Admiralty hoped Howe would no longer feel resignation necessary. Before his replacement could be effected his brilliant powers of leadership repelled the Comte d’Estaing’s French fleet, of twice his number, off Sandy Hook in July 1778. When the French sailed for Rhode Island he followed them, arriving on 9th August but refusing to give battle as he did not want to fight on his enemy’s terms. A violent gale dispersed the fleets but not before Howe’s 50-gun ships harried d’Estaing’s bigger ships back to Boston. After returning to Sandy Hook, Howe went back to Boston on 31st August but by now the French fleet was in total disarray and it was with some satisfaction that he was able to leave America on 25th September.

For the next three years he lived at Porters Lodge, whilst he and his brother defended themselves against claims that they had not prosecuted the war to the best of their abilities. Between January and July 1779 there was much debate in the Houses of Parliament over the Howes’ North American campaign, and in a speech he made on 8th March Howe accused Lord North’s government of distributing false pamphlets denigrating him and his brother and, without a doubt, the North administration considered the Howes’ to be excellent and convenient scapegoats.

It was not until after the resignation of Lord North’s administration, that Howe returned becoming commander in the Channel in 1782, and effecting the Relief of Gibraltar that year. From 1783 to 1788, he was First Lord of the Admiralty, but returned to command the Channel Fleet in 1790, winning the great victory of the Glorious First of June in 1794, capturing six French ships. During his service career, he was particularly active on signals and tactics and is said to have been the first person to lay down a positive rule-of-the-road at sea; that a ship on the port tack should give way to one on the starboard tack. Howe ranks with Anson, Hawke, and Rodney as one of the greatest seamen of the 18th century.

Howe succeeded to a Viscountcy in the Irish Peerage in 1758, was created Viscount in the Peerage of Great Britain in 1782 and Earl in 1788.

The transits of Venus of 1761 and 1769 appear to be the start of the story of this portable astronomical regulator. The planet Venus passes directly between the Earth and the Sun twice every 113 years and, for a few hours appears silhouetted, moving across the bright solar disc. If the apparent position of the track relative to the Sun can be determined as seen from several places of widely differing latitudes, this will give a measure of the radius of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, one of the fundamental distances in astronomy.

The predicted transits of 1761 and 1768 were considered one of the most important scientific happenings of the century and gave rise to many expeditions, which were dispatched to remote parts of the world. The 1761 transit was taken particularly seriously by the British and French governments, but also included the Swedish, Russians and Americans. By 1768 interest had grown and the observations increased, again principally organised by the British and French, and including the Swedish, Russians and Americans but involving Catherine the Great overseeing in St Petersburg with Benjamin Franklin in London and David Rittenhouse in Pennsylvania.

The British preparations for the 1761 transit were in the hands of the Royal Society who bought from Ellicott, one of their own Fellows, a timepiece for £35.8s. Nevil Maskelyne and John Waddington were to be the Society’s observers at St. Helena, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon (the same that later gave their names to the Mason-Dixon line between Pennsylvania and Maryland) were to go to Sumatra, and the Ellicott clock was allocated to the second pair.

Mason and Dixon embarked at Spithead in H.M.S. Seahorse, under Captain James Smith, at the end of December 1760. She sailed for Sumatra on January 9th, 1761. But these were troubled times and the Seven Years War (1756-1763) was in progress. The day after sailing, the Seahorse fell in with a French ship and came under attack with 11 killed and 38 wounded. On limping into Plymouth, Mason reported that the instrument stands were hurt very much, but that the clock, quadrant, telescopes, etc., were not damaged. The Seahorse finally sailed from Plymouth with a new captain on February 3rd, 1761, however, so much time had been lost that going to Sumatra had to be abandoned and Mason and Dixon were landed at Cape Town on May 2nd, setting up the Ellicott clock ashore on May 4th. The transit was successfully observed on June 5th. On the way home Mason and the Ellicott clock were landed at St. Helena to continue the gravity experiments which he had made at Cape Town. Here he met Maskelyne who had sent his clock, by Shelton, to the Cape for the same purpose.

In June 1769, the Ellicott clock was once again present at a transit of Venus, this time being set up the previous September at Prince of Wales Fort, Hudson’s Bay in Canada. On 11th December 1768, with an internal temperature of minus 31°F and an external of minus 42°F, the regulator stopped and was not set going again until March 28th when the temperature had risen to about 0°F. On June 3rd, 1769, the transit of Venus was successfully observed using the Ellicott clock for timing by William Wales (c.1734-1798). It is interesting to note that, in the official account, the clock was referred to as a clock, made by Mr Ellicot, with an apparatus for correcting the effects of heat and cold; the same which Messieurs Mason and Dixon had to the Cape of Good Hope.

In May 1771, Dr. Owen and Mr. Maskelyne presented to the Royal Society Council a list of the observatory instruments used in the various transit of Venus expeditions, together with their valuations. Though the list itself cannot be found, the Council minutes do give the valuations, including £38 for each of two Shelton clocks but no mention of the Ellicott. The minutes go on, Ordered that any member of the Society be at liberty within a month to purchase any of them at the specified valuations, except that those that are intended to be kept for use of the Society. On 19th March 1772, the Council ordered that the astronomical instruments, contained in a list with the valuations, be put up for public auction, but there are no further records of the auction or the Ellicott clock.

Although Admiral Howe never took part in a scientific expedition or voyage of exploration, he was Treasurer of the Navy, 1765-1770, attending board meetings connected with the planning for the 1769 transit and perhaps that sparked his interest in a souvenir? It seems likely that, after the success of the first transit observations, Ellicott was commissioned to produce more portable regulators. Stylistically, this clock with its simple circular dial, rectangular plates, interior pendulum adjustment and squared off case corners, has every appearance of being a little earlier than the other surviving examples. Furthermore, Admiral Howe’s clock is the only surviving portable regulator by Ellicott that appears to lead us directly back to the 18th Century, and the characters involved with the Royal Society portable regulator and the transits of Venus, which is possibly the first that Ellicott produced.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 5827373 cm |

|---|